Since we recently expressed gratitude for the generations of advisors and clients at Park Piedmont, we wanted to highlight one family we’ve been working with for decades.

Bernard (Buddy) Rosenbaum is an Industrial/Organizational Psychologist with a doctorate degree from Columbia University. Buddy began working with Park Piedmont co-founder Vic Levinson before Park Piedmont existed. Though the firm wasn’t founded until 2003, Vic was already advising clients with the same investment philosophy that guides Park Piedmont today.

Buddy Rosenbaum and Vic shared a love for Central Park. “That was our office,” Buddy said recently. “We had a bench in Central Park, and that’s where we would have our meetings.”

Over the years, three generations of Rosenbaums – Buddy and his wife Linda, their three adult children and partners, and now several of their grandchildren – have worked with three generations of Levinsons, making the relationship a special one.

We caught up with Buddy Rosenbaum the week of his 87th birthday, and he charmed us with stories of his life with money – and his remarkable life on a motorcycle.

What is your earliest money-related memory?

My earliest memory of money is getting a wooden vegetable box from Mr. Horowitz, the local vegetable store man, and taking the vegetable box and 30 or 40 old comic books to the local underground subway station.

I set up my stand – the wooden vegetable box – right at the top of the steps where people were coming out of the subway. For new, the comic books would have cost 10 cents, but I was very entrepreneurial. I must have been about nine or 10, and I was selling them for four and five cents.

The following week, another fellow from the neighborhood – Brucey was his name – came with comic books that were in somewhat better shape than mine. He was selling them for the retail price of 10 cents, and he couldn’t understand why mine just flew off the vegetable box and his didn’t. So that’s my earliest money memory.

What is one purchase you’ve made that felt especially weighty – or filled with possibility?

I had a consulting firm, and I brought some partners into the firm. I made a decision at that point that I would treat myself to a luxury item that I had wanted all my life, and I bought a motorcycle.

I was 41 or 42, and it was one of the greatest decisions because my wife accompanied me on many, many tours. We were adventure travelers from that point on. We toured a good part of the world – most of Europe, Nepal, parts of India, Patagonia, South America – all on motorcycle.

A motorcycle opens the world to you, and it opens people to you too. You’re very approachable on a motorcycle. In a car, you’re protected – you have to roll down a window if you want to talk to somebody. But you’re very accessible on a motorcycle, so you get to meet people that normally you would never interact with. And that’s true in the most remote places as well.

Wow, that’s amazing. Was your wife immediately on board?

I wouldn’t say she was immediately on board, but she wasn’t negative about it. We did some local touring – we went up to Nova Scotia, and that was a big distance at the time.

But then I saw an ad – the one and only motorcycle ad probably ever run in New Yorker Magazine. This tiny ad said, “Ride your motorcycle in the Alps.” And I said, “Oh my god. Can you imagine that, Linda? Riding a motorcycle in the Alps?”

So we signed up, and it was a European touring company located in Austria. When we arrived at the airport, Werna was waiting for us, and I said, “Werna, how did the other tours go so far?” He said, “We’ve had no problems.” Great! I later found out we were the first ones he ever did this with.

Linda was involved on a part-time basis at a local travel agency. And it was her idea to represent this motorcycle company in America, so motorcycle touring became her specialty at the travel agency. They’re the world’s biggest in motorcycle touring now – it’s a company called Edelweiss Bike Travel – and she helped to establish them in America. So that was her involvement. She knew more about motorcycles than I did at the end.

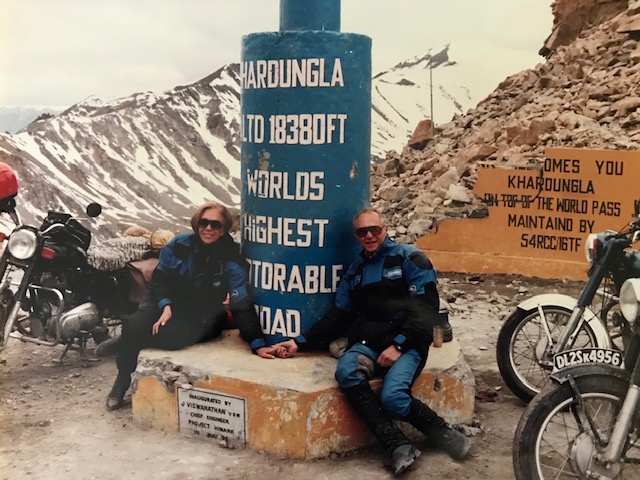

Linda and Buddy Rosenbaum at Khardung La Pass, one of the world’s highest motorable roads, located in Ladakh, India.

Do you have a favorite destination?

Nothing is better than the Alps for riding. We’ve done that many times. But if you expand it to not just the riding challenge but the touring interest, everywhere. We’ve done most of Europe. The longest was with a friend for six weeks. We rented motorcycles and started in Heidelberg, then went up to the northerly most point in Europe, Nordkapp in Norway. We came down through Finland and into Russia, then back through Lithuania and Estonia and so on. But I can’t pick a favorite. We did Patagonia, Nepal, Bhutan…

What do you wish you could tell your 20-year-old self about life with money?

At 20, I knew what I wanted to do with money. It wasn’t the pursuit of money unto itself, but I wanted the freedom that some degree of financial security would provide. The freedom to make choices – not necessarily the choices for survival but for the choices of enrichment.

And I did have a foundational need for security. I got married at a very early age, and we had kids at a very early age. So economic security was very important to me. And all this avocational activity – like the motorcycling – came at around age 40. But up to that point, I was kind of obsessively involved with building my consulting firm. And by the nature of that activity, there was a lot of travel. I was away two to three nights a week for most of that time. And that’s when I brought partners into the business.

Was there ever a decision you made, or a step you took, that made your life with money less stressful?

I think making the decision to bring my partners into the business, which I made pretty early on – somewhere around age 40. It sounds odd: the business wouldn’t necessarily grow in exactly the way I wanted it to, though close enough, but I would also have, early on, some degree of economic security to diversify some of the things I would be doing. I was itching to do some discretionary travel.

What is the best gift you’ve ever received?

Well, I’m thinking about where I am right now [in East Hampton] … A few years ago, my oldest son bought me the world’s greatest beach chair. It had a little umbrella, it had a place for your drink, it had all kinds of different seating positions. Great beach chair! It made going to the beach so much more comfortable. I could strap it onto my back and bicycle to the beach. Terrific gift!

Is there anything else you want to share about life with money?

Meeting and working with Vic allowed me to focus far more on the satisfying and gratifying things in life, rather than checking the New York Times finance section every day. Vic’s investment philosophy squelched the question, “Is the market up or down today?” It was so gratifying, and even liberating, to not have to think about that. So in that sense, there was a liberating dimension of life that came from working with Vic, and now Park Piedmont.